In this article

Producing effective online content is neither easy nor cheap despite what is sometimes suggested.

It takes time and it takes skill. To work, it has to reach its intended audience, meet their needs and interests and support the organisation’s goal. That’s a lot to deliver and as such, it needs to be supported by long term, consistent planning and investment.

Working in museums, what we often see is small teams with limited funds trying to do too much – too many projects, too much content – for ‘all audiences’. Very few organisations have the mechanism to evaluate the value of online content and say – actually no, we can’t do that. Or, if we do x – we won’t be doing y.

At the root of this problem is money: How do we spend the small budget we have in ways that reflect our goals and values? How do we limit what we try to do so we can do it properly and not exhaust ourselves and our teams? How can we increase our funding and what we can achieve? In other words, how do we thrive?

How has Covid changed things?

As the pandemic hit, online teams across the world tried to keep pace as web and social platforms became “the museum experience”. We can’t have been the only ones hoping that the true value of online would be demonstrated in these months and proper funding might follow. Many museums have missions that include engagement, participation and inspiration, all things the web is consistently used for, surely this was online’s time to shine?

Then the scale of the financial crisis became clear and the difficult position of online content – generally offered free – became all too apparent. And so we’ve seen a slew of short-term experiments in online revenue generation and discussions about technologies while staff are furloughed and jobs cut. Organisations need to generate income to survive and, beyond marketing the on-site experience, online content and experiences don’t make a substantial contribution. Tough decisions have to be made.

This raises questions for us about the future of online content and museums. How can we move beyond these small-scale experiments and contradictory actions? What would a more considered future look like that was positive for both audiences and organisations? What would it take to make online content and experiences genuinely sustainable?

What is and isn’t being discussed about charging for online content?

When we started thinking of this series to re-imagine the future for museums and online, we wanted to look at real change – to move away from the endless discussions about technological novelties and tactical solutions and tackle some of the systemic challenges faced by the Museum sector. Dan Hill describes these challenges as dark matter – cultures, processes and assumptions that guide systems that no-one really sees or owns.

Without addressing dark matter, and without attempting to reshape it, we are simply producing interventions or installations or popups that attempt to skirt around the system. This is a valid tactic, but not much of a strategy.

Dan Hill

We felt it was just this dark matter that was standing in the way of positive change around the funding of online content. We thought there were some assumptions and beliefs that limited which opportunities were explored and an over reliance on problematic funding models. So we went out to the community to test that hypothesis and understand the situation better. We posed questions and in response we saw lots of likes and shares, with people keen to see the discussion open up, but little specific feedback. In fact, one anonymous comment suggested that perhaps there is a question about the sectors’ readiness to engage with the dark matter:

“I’ll be interested in what you get back, I don’t think the sector is ready to have this conversation”

Anonymous

Of the handful of people offering something more concrete, Jon suggested:

We wondered if sharing answers in the open felt risky to people – they bring with them compromises that feel difficult or challenging to our core values. Or perhaps as a sector, we have ‘problem blindness’ – we accept the current situation as a given fact of life. But our view is that opening the can of worms and exploring the dark matter is the route to a more positive future.

How do our beliefs shape our actions?

Museums have traditionally favoured three funding models all of which are based on giving online content free to end users. This is the ‘norm’ and it might bring with it some assumptions and ‘problem blindness’. It assumes:

- Offering free online content will by default guarantee the widest possible access

- Charging for content won’t deliver significant revenue (so why try…)

- Existing funding models are doing ok

And maybe, when our confidence is low..

- If we charge for it, no one will use it (and then what will we do…)

- Charging will alienate audiences and funders

Are any of these assumptions true?

Does free online content widen access?

Aren’t museums and online content places where we give people access to knowledge as easily and economically as possible? Isn’t this time of contested facts and culture wars the very moment when museums should be stepping in to share trustworthy information and support people to reflect on their experiences?

We firmly believe that ensuring access to culture, particularly for those who lack social and financial capital, is a vital service but our research suggests that free online content isn’t guaranteeing this right now.

Our recent research suggests that audiences for free online editorial/collections content don’t just look similar to the people who currently visit museums, they are a more concentrated version of museum goers. They are more likely to be white, more highly educated and more frequent museum-goers.

Currently, we use the online space to provide more content to people who are already over-represented and well served onsite.

It could be that it helps these existing audiences connect more deeply with the topic or the organisation, it could be that it improves their well-being or inspires them. That isn’t a bad thing, but it doesn’t support the argument that free content means wider access.

Will charging for content ever deliver significant revenue?

We are not aware of any evidence to prove or, in fact, disprove this assumption. And that’s the thing – it’s just an assumption. It needs challenging and testing. Clearly people do pay for online content and experiences – for entertainment and education.

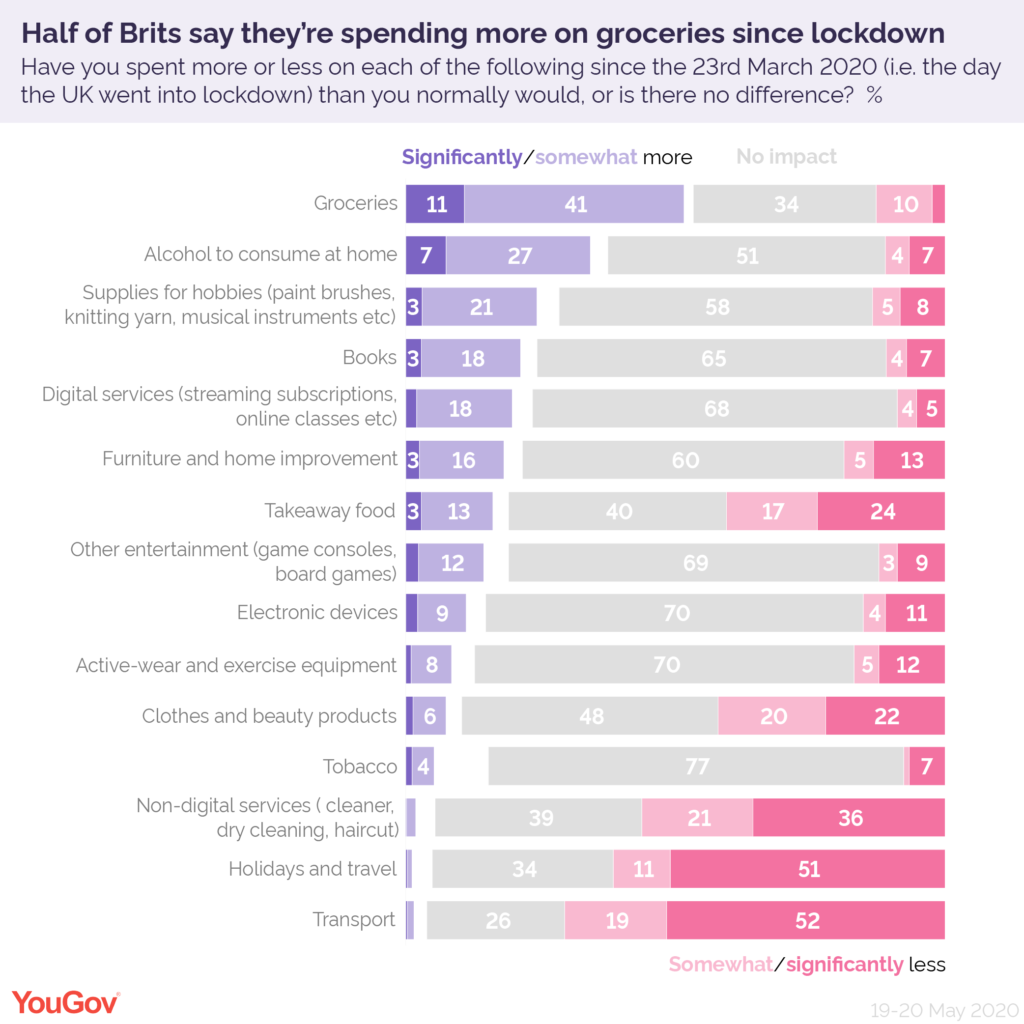

The YouGov research below shows the increase in spending on hobbies, books and digital services. Other research shows a 240% increase in the use of the search term “online learning course” during the pandemic.

So why wouldn’t they pay for Museum content? What would content look like that was so valuable to our audiences that they were happy to pay for it? What investment would it take to deliver? What would the extra income allow us to do?

Are the current funding models are as good as it gets?

Museums have traditionally favoured three models all of which are based on giving content free to end users but they require compromises that affect audiences, our employees and our organisations.

- Cross-subsidy – using core funding and income generated by the in-gallery experiences to deliver online means that quite often online content is dominated by the need to promote or mimic the onsite experience. It reinforces the idea that online is ‘less than’ rather than different. While other sectors see online as a tool to deliver new products and services designed specifically for online, museums have maintained a view that online works in the service of the onsite experience. At the best of times funding is limited and, critically, when the museum is in a financial pinch – like now – online will take a hit. Online teams have little ability to control their destiny.

- Funding (Foundations, Trusts, Innovation Funds) – this funding often comes with an agenda guided by policy rather than the needs of the organisation and audience. The focus for digital is therefore often on building new and innovative one-off products through short term projects. As a result, the products tend to end up poorly managed or maintained once the funding has finished and the less funder friendly backroom work that would really deliver stays under-funded.

- Sponsorship – Support from a commercial – often tech – company to raise or shape their profile. These are often shiny projects that put the need to look new and impressive before providing experiences that are needed by the audience or sustainable by the organisation. They are often led by companies looking to make a splash in the sector and also have a tendency to disappear if they don’t reach the numbers.

Each of these models brings with it some compromises, but Museums have actively avoided some other forms of business models. And they just so happen to be the ones where content is paid for by the end user:

- Donation or crowdfunding – generating income by asking people to buy into and support your mission. For an organisation, it maintains the idea of not creating a barrier between the content and those that can’t afford to pay. However, to succeed you need to demonstrate your mission and focus on the needs of the end users. The Guardian recently announced that it broke even using this model – and it shows how hard it is to get right.

- Paid by end user – If we are asking people to pay, we have to understand them – what motivates them, what they value, how they behave. We have to evaluate the cost and the likely return over time. This could lead to a more robust and sustainable service. The compromise is that it limits access to those who can’t afford it unless it can generate a surplus that supports those vulnerable audiences who really can’t pay.

Will anyone pay? Will we lose our audience?

Charging for access to content isn’t new if you look at the physical visit experience – asking people to spend money on-site isn’t seen as a no-go area. It enables our organisations to invest in and deliver some amazing and valuable visitor experiences. We might sometimes hear grumbles around price point or value for money but there is little alienation.

The business model for paid in-gallery experiences has been developed and refined over many decades. And while it too has its flaws, it gives access to audiences to learn and experience new things.

Yet, we talk about them differently for online and in-gallery, Michael highlights here:

What does all this suggest?

It definitely doesn’t suggest that all online content should be charged for but it does highlight the need to investigate the dark matter that sits behind some of the decision making. It suggests a need for more open, positive and productive conversations that challenge and test assumptions and allow us to genuinely thrive.

We believe those discussions need to centre around these three options, for delivering sustainable and valuable effective online content:

- Shrink what we do: Understand what we deliver that is truly valuable to the audience and the organisation and focus on it to ensure it delivers. Cut everything else

- Invest in what we do: Understand the value it’s possible to deliver, identify the best business model and invest to generate income.

- Keeping doing what we do: Carry on as we are, trying to be everything to everyone, exhausting the staff and potentially missing the big prize

This is the moment to challenge the accepted assumptions, and to use these discussions as a catalyst to be able to demonstrate the value of online content. To stop a move to exploit staff by asking them to increase their workload – and to identify realistic and sustainable models that enable museums to thrive online.

Making online content that delivers so much value to users that they are willing to pay for it, could demonstrate that online delivers value to the organisation. And perhaps this moves online from being the icing on the cake of the physical experience, to being part of the cake itself.

What do we do about it?

Throughout this process, we’ve been clear that we don’t have all the answers and more than likely there is no one right answer. What we do want is to support our community to understand the challenge – what has held people back in the past and what evidence will we need to give us a better vision of how to move forward?

When organisations are feeling the need to act quickly and people are in fear of losing their jobs – it is hard to take a moment to question our own assumptions. But seeing things with new eyes, can inspire us and allow us to imagine new ways of doing things.

When we work with organisations, we are often in a position where they are looking to change but the old ways of seeing are getting in the way. A key part of our practice is to begin to ask questions and find evidence that challenge some of those assumptions and move people to new more open conversations.

Here are some questions to help you begin to have conversations with cross-departmental teams in your organisation:

- What effects are your current funding models having on your capacity to deliver online content? Aim for an open and honest conversation about how projects and online content is currently designed to meet the needs of whoever/whatever is paying and what the compromises might be.

- What would online content look like for our audiences, if it was true to our mission?

- What would it take to break even? How many users and at what price point? What are the start up costs to test the idea?

- What will happen to the income generated? Can this new income enable you to experiment? Can it help you to invest in content or experiences for audiences who aren’t currently represented?

- What do and don’t you know about your potential target audiences? What are their attitudes to paying for online for learning or entertainment? What are they interested in learning or enjoying? What decisions do they make when they purchase? What do they value? How do they find online content they are interested in?

- What kinds of service will this online content provide? Will it help people engage with their hobbies? Will it help them to connect with people they care about? Will it help with their well being or to develop new skills?

This is article is part of our The Real Change Series. In this time of crisis we need to re-imagine our future.

At FG+W, we know the Museum community is having to make difficult choices and decisions. Having lost most of their income, organisations will need to decide what is essential and what isn’t. These decisions and choices will inevitably reflect the values and beliefs of the organisations and have long lasting impact.

Over the next 6 months, we’re going to be – with your help – exploring, re-imagining and re-shaping what comes next for cultural heritage online. We’re hoping to work with you, our community, to explore the question, “How might we use this moment of disruption we all experiencing to bring about positive change in the sector?”

Follow us on Medium, LinkedIn, Twitter and Instagram to join the debates.

We look forward to these discussions with you and the community to help us all get to some real change for the future.